- Home

- Jodi Thomas

The Widows of Wichita County Page 8

The Widows of Wichita County Read online

Page 8

Meredith thought of his third rule as he knocked on her door. This was a professional call. Nothing more. The principal at the grade school probably phoned him, reporting no one had seen her since the funeral. Principal Pickett might be worried and influential enough to ask the sheriff to take action.

Meredith curled back into her chair. She was not interested in talking to anyone. No amount of talking would change anything. She just wanted the world to go away and let her be unhappy all by herself.

The sheriff knocked again, then tried the doorbell as if it would make any difference.

"Go away," she whispered. "I don't want to get involved personally." From now on she planned to take the sheriffs third rule to heart. A week had passed since Kevin's death and she could not stop the hurt inside. If she learned anything, she had learned caring is not worth the pain that follows. From now on no one would come close enough to be more then a "Hello" friend.

After waiting a few minutes, he finally stepped off the porch. He took a few steps down the walk, then noticed the old Mustang parked in the garage. The same car that was usually parked next to his at the courthouse when she worked on holidays while the county clerk's office was closed. On those days he would stop by to let her know someone else was in the building. She always passed his office and told him she had locked up when she left. That had been the extent of their communications before the night at the hospital when he held her tight to keep her from falling.

But, he had only been doing his job as he was now and Meredith did not want to be part of his duties.

They were considerate strangers, she thought. Saying hello to one another at work. That was enough.

She heard him step onto the back porch and knock at the rear door. The sound echoed through her little house.

"I'm not answering," she whispered once more. "I don't want to see or talk to anyone, Sheriff. Not even a considerate stranger like you."

To her shock, he ventured further without probable cause of crime. He tried the doorknob. She had seen enough cop movies to know he was not following the rules.

She closed her eyes, pretending she did not hear his footsteps coming inside her house.

"Meredith?" he called. "Are you home, Mrs. Allen?"

Don't make a sound, she thought.

The sheriff swore beneath his breath as he tripped over the mop just inside the back door.

"Meredith," he shouted as he moved through the clue tered house. "You've got to be in here. No one would leave the heater turned up so high. It has to be eighty in the place."He caught his foot on one of the kitchen chairs. "You must be alive. If you were dead, you'd smell in this heat in no time."

He drew a deep breath. "As it is, it smells like dying potted plants in here."

She wondered if he always talked to himself or if he was keeping a running dialogue so that she would hear him coming and not be afraid.

He rounded the bar and entered the shadowy living room. For a moment, he did not see her hidden within the furniture. She sat perfectly still hoping he would yet go away.

"Meredith?" His feet crunched atop dead leaves as he moved around crumbling sprays that had filled the church a week ago. White mums, limp and brown tipped, were all that clung to the wiring of once beautiful arrangements. "Meredith!"

She did not move.

Slowly, he neared. Crouching beside her chair, he touched her arm.

She finally looked up at him.

"Evening, Sheriff Farrington," she said in a voice that sounded dry.

"Evening, Ms. Allen." He smiled out of relief. "How are you tonight?"

"I'm fine," she answered, "and you?"

"I was a little worried about you." He moved so he could see her face better in the pale light coming through the Venetian blinds. "Folks seem to be having a little trouble reaching you. You're not answering your phone."

"I haven't heard it lately." She glanced at the phone on the table beside her. The cord was wrapped around it. The plastic plug that should have been in the wall reflected the streetlight's glow.

The corner of Granger's lip lifted once more. "Got tired of the ringing, did you?"

She nodded. "Everyone kept calling, saying how sorry they were that I lost my husband. I didn't lose Kevin. I buried him."

"I know. I was there. It was a real nice service." He patted her arm awkwardly. He looked as if he would rather be handling a bar fight than be here talking to her.

Meredith smiled up at him. "I planned the service all by myself. I figured it was the last thing I'd ever do for Kevin."

"You did a good job." Granger said. "You had anything to eat today, Meredith?"

She glanced down as she tried to remember. The area surrounding her chair looked like a snowbank made of tissues. Her legs were curled inside a huge jersey of Kevin's. She touched her long hair, now matted and plastered against her scalp.

"I had some of Mrs. Pickett's pie yesterday, I think." She closed him out and settled back into the folds of the chair. "I've been so cold. So cold."

Meredith folded into her own world, turning her face away from him. All she wanted was to sleep and make the world go away. She had been too tired to even think about her class. In truth, she felt too tired to even sleep.

Without warning, Granger grabbed her by the arms and pulled her to her feet in one quick jerk. "Meredith!"

For a moment she remained limp, like a gelatin doll. He tightened his grip, as if willing her to respond. "Meredith! You are not one of those wilting mums. Come on. Snap out of it. Kevin is the one who died, not you."

She took a deep gulp of air as though he had pulled her from beneath water. Awkwardly, she stiffened, bones straightening. Her legs took her weight.

She tried to pull away from him. How dare he come into her house and remind her that her husband had died? Did he think for one minute, for one second, that she had forgotten? She gulped in air wishing she knew how to fight Never in her life had she wanted to hit someone, to hurt someone, so much.

He backed away a few feet and watched her. "Sorry. I didn't mean to startle you." He tried to brush away the pain he had inflicted from her arms. "I didn't hurt you, did I?"

"I'm all right, Sheriff." Rubbing her arms she tried to decide if she hated him or needed to thank him. "You don't have to worry about me. No one has to worry about me." She suddenly wished she knew all the words to tell him to go away. Who did he think he was, breaking into her house, shaking her, reminding her she did not die with Kevin?

"Stop staring at me that way. I didn't mean any harm, Meredith. To tell the truth I don't even know what got into me, shaking you like that. I just couldn't stand seeing you curled up, giving up. Not you." He looked like he wanted to run, but he forced himself to face her. "How about I go pick up something for supper? Maybe if you ate somethingg you'd feel better."

She stared at him thinking he might just be the strangest man she had ever met. She would bet he never planned to touch her and the fact he did bothered him more than it bothered her.

"I thought, if you'd join me, I could be back in thirty minutes with some food. You'd have time to take a shower while I'm gone." She did not answer. "The hot water might warm you up and save a little of your heating bill."

When she did not comment, he unlocked the front door.

"If I come back and the door is locked I'll know your answer is no to my offer for dinner." He walked out without waiting for an answer.

Thirty minutes later he was sitting at her kitchen bar with hamburgers and malts when she walked out of the bathroom.

"I feel better." She admitted as she pulled her robe tighter and tossed her wet hair back. "What did you bring?"

He stared at her as if he'd never seen her before. Surely her thick robe was not that different from the sweaters she usually wore. But he seemed to be studying every detail about her.

"You did bring food?" she asked, as she moved around him and opened the sack.

"I didn't know what you liked," he finally said. "I p

icked up a couple of cheeseburgers from Jeff's."

Meredith climbed onto the stool beside him and waited.

He handed her a cheeseburger, then a malt. They ate without conversation. She had no clue about what to say to a sheriff. If she had ever committed a crime, she might confess. It did not seem polite to ask about his job. She was not sure she wanted to know who in town had been arrested lately.

When she finished, she went to the refrigerator and returned with a cake someone must have brought over. Funeral food, her grandmother used to call it. Friends and neighbors in small towns always baked their favorite dish and brought it to the house. It did not seem to matter that "the house" only contained one person who could not possibly eat a counterful of sweets and ten pounds of chicken. It was tradition.

She cut them both a slice and returned to her chair.

He pushed the dessert around with a fork without tasting a bite. Finally, he looked at her, and seemed to be studying her face with great interest. He lifted his napkin, leaned over and wiped the top of her lip.

Chocolate malt stained the white of his paper napkin.

She could have written the action off to instinct, but she guessed the sheriff had never done such a thing to anyone in his life.

"Thank you," she said.

For a moment, he did not say anything. He seemed io realize what he had done. He was not a man who touched easily and he had touched her twice in less than an hour. The cake forgotten, he stood.

"Anything else I can do before I leave?" he said awkwardly.

Meredith yawned. "No. I think I'll go to sleep now. Thanks for the dinner."

With him still standing in the middle of her kitchen, she walked the few steps into the bedroom. She lifted the covers and crawled into bed, still wearing her robe.

She heard him shoving food wrappers into the trash. Since he showed himself in, she figured he could show himsell out.

"I'll lock up when I leave," he said, the same words he had said to her many times when they both worked holidays at the courthouse.

When she did not answer, she heard him step to her door. She snuggled into the pillows too exhausted to care what he talked about.

He pulled the quilt over her shoulder. "Good night, Meredith."

"Good night, Sheriff," she mumbled, too near sleep to say any more.

A hand was dealt in a no-name saloon in '27. Three oilmen passed the time playing poker with a local farmer. Money centered on the table. Cards were shown. Guns were pulled from both boot and vest.

When the smoke cleared all four were dead, bleeding across the five jacks facing up from the deck. The deaths were ruled an accident.

October 28

9:00 p.m.

County Memorial Hospital

He felt her presence even before the perfume that was always Randi penetrated his consciousness. She said she wore it because it was the only one she had ever found that could survive in bar air.

Through the thin bandages he saw her tall, slim, cowgirl shadow moving toward him. She made his blood warm from the first day he spotted her in the middle of a line dance at Frankie's Bar. He wished he could move closer to her, now. He needed to touch her. She was the kind of woman who drew a man's hands.

"Hello, Shelby," she whispered in a voice that was made to sing country-western songs. "I'm not supposed to be in here, but I had to drive back to pick up the rest of my stuff. I figured, what the hell, I'd stop by and see you on my way out of town."

She stood just out of his reach.

"I don't know if you can hear me, but I need to say something. I won't feel right until I do." She crossed and uncrossed her arms. The plastic of her leather-look jacket made a popping sound.

He smiled. Randi was all pretend, always had been. Pretend leather, pretend fur, pretend love songs. She had probably pretended with half the guys in town, making every one of them believe he was the first, or the second anyway.

Back years ago, when she and Crystal were running wild and single, every man in the bar knew the party had started when they walked in. Crystal, with her baby-blue eyes, may have had her beaten on looks, but when a man danced with Randi, he left the dance floor feeling like the foreplay was about over.

Her low voice whispered over the machines. "I need to tell you about that first day, when the doctor brought the ring in. I couldn't be sure if it was yours or Jimmy's. You both wore that plain band Taylor's sells to just about every man. It was so out of shape, it didn't look much like a ring at all. With you and Jimmy looking so much alike, you being kin and all, it was impossible for the hospital to tell. You two even had the same blood type. Folks always said he seemed more like your son than Trent ever did. He even told me once he thought he'd been following you around since he could walk."

She rocked from her toes to her heels. "I guess what I'm trying to say is the hospital thought it would be easier if we just identified the only husband alive. Crystal wanted you to be Shelby so bad, and me…"

He relaxed, guessing what she was about to say.

"I was never meant to take care of an invalid, much less be stuck in a small town. We don't even have insurance to cover any hospital bills." She clicked her nails along the metal frame of the fancy bed. "I was packing to leave when the accident happened. Healthy, Jimmy wasn't worth much. If he was hurt bad, I don't think I could…"

He closed his eyes, no longer wanting to look at her. Randi was a woman who always divided the pie in her favor.

The most important person in her world lived in her skin. He could never hate her for that. With Randi, it was like instinct. Self-preservation. She would never change.

"Well…" She sounded nervous. "I just came by 'cause I've been thinking. What if there was a one in a million chance you were Jimmy and not Shelby under all those bandages and burned skin? After all, once Crystal took the ring, there were no further checks and everyone knew Shelby had a thing about never going to a big hospital. So there was no thought of transferring him."

She pulled a pack of cigarettes from her pocket, hesitated, then put it back. "If you are Jimmy, I figured I should tell you the score. You've got a chance to come back from this as Shelby Howard and do a lot of good for yourself. You could be like the old legend of that bird and rise up out of the ashes to fly. If you're Jimmy and anyone finds out, you'll probably spend the rest of your life in a welfare hospital. But Crystal says she's already ordered thousands of dollars worth of stuff to take Shelby home and give him the best of care."

She glanced at the door. "I got to go. There's a sign outside that says no one but family. If you're Shelby, I wish you the best. If you're Jimmy…"

Sniffing, Randi dug a balled tissue from her jeans pocket. "If you're Jimmy, keep your mouth closed and do us all a favor. You weren't a bad husband. I just couldn't love you like you wanted. It ain't nobody's fault."

A rattle sounded at the door. She slipped into the blackness. A nurse came in to pull the blinds and shift his position.

"Looks like a storm is moving in, Mr. Howard." She straightened his arms, making his body mold to the airplane looking splints. "Now don't you worry, that little wife of yours will be back in a minute. The only time alone she gets is when she takes her bath, and we want her to take her time and enjoy it."

He hated it when the nurses talked like that, as if he were a child, as if they knew how he felt or what he thought.

The nurse checked the machines. "Hope the rain don't keep you up, Mr. Howard. We're suppose to get a storm tonight. The wind's already whirling around so bad even the weatherman can't make up his mind which direction it's coming from."

She left the room without expecting him to comment.

A moment later, the door opened enough for a thin cowgirl to pass through.

He closed his eyes and wished himself dead for the hundredth time since the accident.

Old-timers used to swear that if a sane man settled on the plains, he would be driven mad by the wind before he made it through his first winter.

/> October 28

Midnight

Montano Ranch

Thunder rumbled across the land in low angry bellows. Anna Montano wrapped her arms around her waist and tried not to jump each time she heard the sound. Pacing back and forth across the wide living room, she wished the walls of her ranch house were not constructed mostly of glass. At sunrise and sunset she thought the view beautiful, but now, with lightning flaring, all she could think was that the windows might crash in on her at any moment.

The reverberation reminded Anna of her childhood when her father's voice often echoed with rage off the tile walls of their villa. His solution to all disagreements was a swift and physical reaction. He would draw his belt with the precision of a gunfighter brandishing his Colt. The sons were trained to stand and take their punishment. But Anna learned to hide away, to remain silent, to become invisible. It was the way she, as the only daughter, survived.

As she grew older, she realized her father knew she was tucked away just out of his sight, curled in some shadowy corner. His pride would not allow him to pardon her but, silently, he permitted the game.

Her brother Carlo's storms of rage were nothing compared to their father's, but Anna feared that by the time Carlo fathered children he would mirror the generation before Since she and Carlo had been in America, her brother turned his anger more on the hired hands and less on her.

In fact, he had fired a ranch hand the morning before the rig exploded. Anna watched from the window as Carlo not only ordered the former employee to leave, he half dragged, half beat the man all the way to his car.

The man swore he would be back to even the score, but Carlo only laughed, welcoming a rematch. The threat made Anna shiver, not from fear of the stranger, but from how far her brother might go if the man set foot on Montano land again.

On the few occasions she had been the target for Carlo's anger, her husband, Davis, had done nothing to interfere. He allowed Carlo to yell and swear at her in two languages with little more interest than a bystander watching a parent discipline a child. She had been so young when they married, she knew he and Carlo saw her as little more than a child and probably always would.

The Valentine's Curse

The Valentine's Curse Christmas in Winter Valley

Christmas in Winter Valley A Texas Kind of Christmas

A Texas Kind of Christmas Breakfast at the Honey Creek Café

Breakfast at the Honey Creek Café Cherish the Dream

Cherish the Dream Boots Under Her Bed

Boots Under Her Bed The Cowboy Who Saved Christmas

The Cowboy Who Saved Christmas Easy on the Heart (Novella)

Easy on the Heart (Novella) One Wish

One Wish Texas Blue

Texas Blue Be My Texas Valentine

Be My Texas Valentine Can't Stop Believing (HARMONY)

Can't Stop Believing (HARMONY) Mornings on Main

Mornings on Main Promise Me Texas (A Whispering Mountain Novel)

Promise Me Texas (A Whispering Mountain Novel) To Kiss a Texan

To Kiss a Texan Sunrise Crossing

Sunrise Crossing One Texas Night

One Texas Night Two Texas Hearts

Two Texas Hearts Somewhere Along the Way

Somewhere Along the Way A Texan's Luck

A Texan's Luck Texas Rain

Texas Rain The Texan's Reward

The Texan's Reward Wild Horse Springs

Wild Horse Springs Forever in Texas

Forever in Texas Mistletoe Miracles

Mistletoe Miracles Prairie Song

Prairie Song Indigo Lake

Indigo Lake A Christmas Affair

A Christmas Affair Rustler's Moon

Rustler's Moon Beneath The Texas Sky

Beneath The Texas Sky Texas Love Song

Texas Love Song The Texan's Touch

The Texan's Touch Welcome to Harmony

Welcome to Harmony To Wed In Texas

To Wed In Texas The Widows of Wichita County

The Widows of Wichita County The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home The Texan and the Lady

The Texan and the Lady Chance of a Lifetime

Chance of a Lifetime The Secrets of Rosa Lee

The Secrets of Rosa Lee Twisted Creek

Twisted Creek Winter's Camp

Winter's Camp Twilight in Texas

Twilight in Texas Just Down the Road

Just Down the Road The Lone Texan

The Lone Texan Give Me a Texan

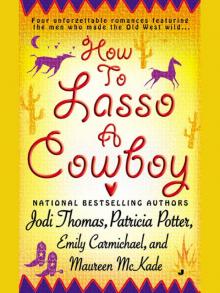

Give Me a Texan How to Lasso a Cowboy

How to Lasso a Cowboy Wild Texas Rose

Wild Texas Rose Finding Mary Blaine

Finding Mary Blaine