- Home

- Jodi Thomas

The Valentine's Curse Page 2

The Valentine's Curse Read online

Page 2

“Please tell Mrs. Molly Clair that I’m happy here watching. I don’t need to join the group and I don’t need anyone sitting with me. I’m quite used to being alone.”

Brody nodded his understanding. “She said if I didn’t sit with you or dance that I was fired. If you’ve no objection, I’d rather sit with you.”

“Suit yourself.”

They watched for a while, and then he rose and disappeared as silently as he’d come. Valerie shrugged. In truth, she kind of missed his company. The strange man seemed a cut above most of the men there. He hadn’t flirted or tried to force conversation.

When he returned carrying two plates of sandwiches with desserts piled on top and two coffee cups, she was surprised.

He sat the plates and cups down between them without looking at her.

“Mr. Monroe, I believe I said I didn’t want anything.” She was always irritated by men who thought they knew what was best for her.

He glanced up from his plate as if just noticing she was still at the other end of the bench. “I know. They’re both for me. I’ve been out on the range and haven’t had anything but hardtack for days.” He hesitated. “I don’t mind getting you something when you decide you’re hungry. If you’ve no objection, I’d like to continue sitting here for a while.”

“Don’t you want to dance with a pretty young girl?”

“No.” His answer came out cold and solid.

Valerie watched as he finished both plates and all the coffee. “Feel better?” She smiled despite her irritation that he’d obviously been sent to baby-sit her.

He stood, lifting both cups as if to say he needed a refill. He circled behind other people sitting around the fringes of the dance floor and headed to the refreshment table.

A few minutes later, Emma Lee Cooper walked by as if on the way to somewhere and just happened to notice Valerie in her path. “Evening,” she said, her smile sweet but uncaring. “I noticed you talking to the Yankee. That’s mighty broad-minded of you, seeing as how his kind killed both your husbands.”

Valerie looked down at her calloused hands, wishing she’d remembered her gloves, as she answered her childhood friend. “He was just sitting on the other half of the bench.” She hated herself for even trying to explain. Emma Lee and her friends would say or think anything they liked; they always had. Sitting beside a Yankee couldn’t do her reputation any more damage. “The war’s over, Emma Lee. It has been for two years.”

“I know, but my Earl says that Brody Monroe is a strange one. Says he never talks to anyone, and even when they play little games on him, he won’t fight back or even say anything. Maybe he’s a coward and that’s how he survived the war.” She looked out at the dancers as if bored by her own conversation. “He is good-looking, I guess, in a hard kind of way.”

“Maybe.” Valerie wanted to defend this man she didn’t even know, but she didn’t dare. “What kind of games do the men play?”

“Oh, you know, the usual. Passing food around and always making sure the empty plate ends up at him. Sliding a burr under his saddle to make the day start with a wild ride. Always forgetting to tell him when the boss says they can sleep past dawn.”

“Earl said after a while they quit just because they could never get a rise out of him. He’s like a walking dead man, no emotions, no feelings.” She waved at one of the men standing by the small band. “You’re probably the only woman here who’d let him get close enough to sit down. My Earl and his brother, Montie, told me they’d knock the guy out if he even tried to ask me or my friends to dance. The Timmons boys are the kind who’ll take care of a girl.”

Valerie almost said she didn’t want that kind of man. She’d had two who’d promised and hadn’t.

“Earl Timmons is a thoughtful man and handsome, too,” Valerie lied. She had nothing against the man other than he probably had to prime his brain to get it working every morning.

“Yeah, I know.” Emma Lee grinned. “He or that brother of his is going to marry me. I just haven’t figured out which one. Belle Wallace says she’ll take whichever Timmons is left over. She’s not picky like me.”

Emma Lee must have seen Brody coming, because she darted back the same way she’d come. A moment later the tall cowboy sat down.

“I brought you a refill,” he said as he set the cups between them.

“I didn’t drink the first one.”

“I know.” He watched Emma Lee rushing into Earl’s arms. “That girl tell you not to talk to me?”

“Yes.” She watched him take a drink. “Did someone tell you to stay away from me?”

“Yes,” he answered without hesitation. “Pretty much everyone who has talked to me tonight. Even one of the ladies cutting pie asked me how I was feeling, then glanced over at you.”

She smiled. She wasn’t sure who this man was, but she knew two things about him already. He wasn’t afraid of her, and she wasn’t afraid of him. She lifted the second cup of coffee and took a sip. “To honesty,” she whispered. “Thanks for the refill.”

“You’re welcome.”

When she set the cup down, she asked as she fought down a smile, “How are you feeling, Mr. Monroe?”

“Couldn’t be better, Mrs. Allen.”

She wished she could say they had a long talk, but they did manage to say a few things to each other. Her father stopped by and seemed pleased that at least one man in the room talked to his daughter. He asked Brody where he was from, and when he said Ohio, her papa nodded and commented that he was from Ireland and he guessed that would be a bit farther away.

Papa rested for a few minutes, then headed out on the floor. He reminded her of someone who saw death coming for him and planned to run as long as he could. The doctor had predicted if he retired and stayed home, he might live five or more years. Her papa had laughed and said he’d take his ticket to heaven when it came and there would be no hiding from it. As she watched him dance, Valerie had to smile. He was making the most of the time he had left, and she wouldn’t nag him to slow down.

When the band leader announced the last dance, everyone in the barn hurried onto the floor, knowing there would be no more dancing for months.

Everyone except the two people on a bench in the shadows.

Valerie gathered up her shawl. “I think I’ll leave before the rush. Thank you, Mr. Monroe, for the coffee.” She almost added, “And the company.” Though he hadn’t talked, there had been a calmness between them, a simple awareness of another person like themselves in the world.

He stood, followed her into the darkness while everyone shouted as the music started. “I’ll walk you to your wagon,” he said. “If you’ve no objection.”

“I’ve no objection.” She slowed. When he caught up beside her, Valerie linked her hand at his elbow.

She felt him stiffen and wondered how long it had been since anyone had touched him. Or, she smiled, was it possible this hardened cowboy could believe in a curse? She’d heard what they said about her.

A little girl at the door handed each a paper heart as they passed. Valerie put hers in the pocket of her skirt, and Brody folded his into his vest. Neither wanted them, but they didn’t want to hurt the little girl’s feelings by tossing them away. Valentines were for children and lovers, not for the likes of them.

Awkwardly, he covered her hand with his and moved through the night to the line of wagons near the corral. A few lanterns glowed between them, offering a night light for children already asleep in the wagon beds.

When they reached her father’s big box of a wagon, Brody hesitated and Valerie laughed. “My father is the local carpenter. He thinks he has to take his tools with him everywhere he goes, just in case he’s needed. You’d be surprised at how many people bring broken furniture for him to haul home and repair. The dance saved them a trip into town.”

Brody looked in the back. “Looks like business is good.”

He offered his hand to help her up. “How long have you been a widow, Mrs. Allen?�

��

“A little over three years.” She didn’t look at him as she gathered her shawl tightly across her shoulders.

“And you still wear black.”

She couldn’t tell if it was a statement or a question. “I’ve little hope to marry again. The black serves me well, even though I doubt I’d have a male caller after all the rumors spread about me.”

“You have land. There are some who might ignore the rumors and marry you for it.”

Valerie shook her head. “Would you?”

She had the feeling she’d embarrassed him and was glad she couldn’t see his face. “I’m sorry. Everyone says I speak my mind too quickly for it to be ladylike. I didn’t mean—”

“I’m not the kind of man you’d want,” he broke in. “I got nothing to offer any woman.”

She recognized the hollowness inside him. Like her, he had nothing to give. He just wanted to live out his days. Maybe like her, he was afraid even to dream.

“Thank you for sitting with me, Mr. Monroe.”

On impulse she rose to her tiptoes and planted a light kiss on his cheek. “I wish you peace.”

“The same to you, Mrs. Allen.” Then he took her hand and helped her up into the wagon. While she waited, he checked the harnesses and made sure the wagon would be ready when her father arrived.

She sat in the darkness listening to the last song and wishing she were already home. As the barn dance broke up, people spilled out into the night. Couples who’d been dancing together were now hugging as they moved through the shadows whispering farewells. A few families had brought bedding to sleep in the loft, and Mrs. Molly Clair told the single girls they were welcome to spend the night at the house.

She hadn’t included Valerie in the invitation. Valerie told herself it was simply because Mrs. Molly Clair knew her papa would pass by her place on his way home. He’d see she was safe and Valerie knew she didn’t belong with the young women.

She suddenly felt very old.

She wouldn’t have stayed even if she’d had to ride home alone. The women who had once been her classmates and friends were now little more than strangers. She feared they avoided her because, for a girl looking for a man, she was a reminder that happily-ever-after existed only in fairy tales.

Valerie looked in the direction Brody had gone toward the corral. She knew, without thinking why, that he was standing in the night watching her.

Most people were driving toward the road when her father appeared at her side of the wagon. “There you are, my Valerie. I was thinking you’d probably sneak out early. If you don’t mind waiting, I got to go to the main house and pick up Mrs. Molly Clair’s sewing machine. It won’t take me but a few minutes and it’ll save coming back out to get it.” He must have seen her look, for he added, “Now don’t you worry, she’s already told two of the men they’ll be hauling it out and putting it in my wagon.”

“I don’t mind waiting.” The thought of going into a house full of giggly girls, some only a few years younger than her, frightened her. At times the whole world frightened her. For as long as she could remember, all she’d ever wanted was a home and family of her own, but the goal kept slipping through her fingers like sand.

Suddenly sorrow smothered her and all the what-might-have-beens pushed against her lungs like an anvil’s weight on her chest.

She swung down from the wagon and ran into the blackness near the corral. Part of her wanted to dive into the shadows and drown. She wasn’t ready for all the rest of her life to simply be just a vase for the keeping of a few memories and the shattered fragments of what might have been.

A strong arm caught her suddenly and swung her around.

She jerked, pulling away for a moment from the man who held her. The outline of a fence and the low sounds of horses circling just beyond registered a moment before the man pulled her against him. “Take it easy,” Brody whispered. “You’ll startle the horses and get hurt.”

Valerie gulped for air. She expected him to let her go, but he stood near, not holding or moving away.

Before she let reason rule her life, she whispered, “Hold me. Just for a minute, please would you mind holding me?”

Strong arms came around her and pulled her so tightly against him she could barely breathe. For a while, he just held her; then he leaned down and kissed her forehead.

She felt herself shaking, but she didn’t pull away. She needed, more than air, to have someone hold her like he’d never let her go. She wanted to believe in forever between two people if only for one more moment.

Slowly, his hand moved along her spine, pressing her against the length of him. His warm breath moved in her hair as she leaned her cheek against his throat.

She wasn’t sure if they held each other for a few minutes or more, but when she heard her father and a few other men coming, she pulled away and he vanished back into the night as if he’d been no more than smoke.

She was beside the wagon by the time her father opened the back and told the men where to put the machine. All the way home Papa talked as she tried to remember every second she’d had in the darkness with a man she barely knew.

People might not want to have much to do with her, but they all loved visiting with her papa. From making cradles to caskets, he was in their lives, and his favorite thing to do when all the others had gone was to repeat to Valerie everything they’d said to him. So he talked and she remembered as they rolled down the road.

When he was within sight of her farm, he finally said something about her. “You know, Boss told me tonight that he’d buy Venny’s place if you want to sell. Couldn’t pay much, but it would be cash. Then you could move to town and live with me. I’d build you a little house out back with lots of glass so you could grow a garden year-round.” He slowed the horses. “I’d enjoy your company, and a woman shouldn’t be living alone way out here.”

Valerie had lived at the farm since she married Venny eight years ago, but her father still saw the place as her first husband’s. When Venny left for the war after the first year they were married, her father wanted her to come to town. When her first husband had been killed six months later, Papa had tried again but without success. She’d lived alone for three years before Samuel, a doctor serving with Terry’s Rangers, was home on leave and asked her to marry him. They’d married a day before he’d left to go back, and he’d laughed, trying to sound like her father as he said she’d have to move to town with him as soon as he returned.

Only his body was all that came home months later and her father talked of her moving back even as he built Samuel’s coffin.

“I’m not selling, or moving, Papa.” She wished she could add that she was happy where she was, but they both knew that wasn’t true. What her father didn’t understand was that she would be no happier in town. At least with all the work of the farm, she was usually too tired to even cry herself to sleep most nights, and when she did, there was no one a room away to hear her sorrow.

As she climbed down, she patted her papa’s hand and said, “Thanks for making me go. I enjoyed the music.”

“Was everyone nice to you tonight, dear? ’Cause if they weren’t, they’ll be rocking their babies in shoe boxes and be buried in a blanket when they die.”

“Everyone was fine.”

“And the cowboy who sat down next to you? He didn’t say nothing wrong, did he?”

“No.” She thought of adding that he didn’t say anything much, but then she remembered the way he held her and decided it best not to talk about him at all.

She went inside her little house and crawled into bed trying to remember exactly how it had felt to be held by someone again.

Chapter 3

Brody Monroe stood in the moonless blackness by the corral for over an hour thinking that if he didn’t move, maybe, just maybe he could keep the memory of how Widow Allen had felt in his arms. Wind whirled around the barn as if trying to blow any feelings away.

Finally, he turned and headed to the bunk

house. Within three steps, he tripped over a downed fence post. Like a tumbleweed, he rolled in the dirt until he hit the barn wall.

Brody swore at himself for being so careless. He was still dusting himself off when he stepped into the bunkhouse five minutes later.

Most of the men were still up talking about the dance. Earl Timmons glanced at him. “See you survived meeting the widow.”

Brody nodded once and kept walking.

“Lucky you didn’t touch her, Yank, or we’d be picking up the pieces of you. I once heard a fellow say he got a blister the size of a silver dollar on his hand from just pointing at her.”

“He wouldn’t touch her,” one of the men behind Brody commented. “He don’t even shake hands if he can help it. The Yank don’t have a friendly bone in his body.”

Brody kept walking. They didn’t need him there to continue talking about him. He pulled off his good clothes and crawled into his bunk. For once, it was a long time before sleep found him.

As the days passed, he tried to stop thinking of the woman he’d met at the dance, but she was never far from his thoughts. In a strange kind of way, she pushed away the loneliness he’d grown so accustomed to. She had a pride about her that he admired. What people said about her didn’t seem too important.

She wasn’t his, she never would be, but a part of her, for a moment in time, had been his, and one memory was enough to build daydreams on even though he knew there would never be more. It probably would have frightened her to know how few times in his life he’d held a woman. Those experiences had been before the war, and they seemed more a dream than real. After the war the only kind of woman who’d pay a drifter any notice wasn’t the kind of woman Brody wanted to hold.

Once, months after the war, he’d found a short job that had left him with money in his pocket. He’d thought about buying a three-dollar whore for the night, but he’d elected to build a supply of food instead. Now, thinking about holding Mrs. Allen, he was glad her memory didn’t have to blend with one he’d bought.

He’d overheard someone mention the carpenter and his daughter a few times. Brody knew she lived between the ranch and town, but he had no idea which place. Half the farms looked abandoned. The war had added a layer of poverty over almost every part of Texas, and taxes were drawing away any extra money for repairs. The cattle drives last summer had helped, but it would take years before people got back on their feet.

The Valentine's Curse

The Valentine's Curse Christmas in Winter Valley

Christmas in Winter Valley A Texas Kind of Christmas

A Texas Kind of Christmas Breakfast at the Honey Creek Café

Breakfast at the Honey Creek Café Cherish the Dream

Cherish the Dream Boots Under Her Bed

Boots Under Her Bed The Cowboy Who Saved Christmas

The Cowboy Who Saved Christmas Easy on the Heart (Novella)

Easy on the Heart (Novella) One Wish

One Wish Texas Blue

Texas Blue Be My Texas Valentine

Be My Texas Valentine Can't Stop Believing (HARMONY)

Can't Stop Believing (HARMONY) Mornings on Main

Mornings on Main Promise Me Texas (A Whispering Mountain Novel)

Promise Me Texas (A Whispering Mountain Novel) To Kiss a Texan

To Kiss a Texan Sunrise Crossing

Sunrise Crossing One Texas Night

One Texas Night Two Texas Hearts

Two Texas Hearts Somewhere Along the Way

Somewhere Along the Way A Texan's Luck

A Texan's Luck Texas Rain

Texas Rain The Texan's Reward

The Texan's Reward Wild Horse Springs

Wild Horse Springs Forever in Texas

Forever in Texas Mistletoe Miracles

Mistletoe Miracles Prairie Song

Prairie Song Indigo Lake

Indigo Lake A Christmas Affair

A Christmas Affair Rustler's Moon

Rustler's Moon Beneath The Texas Sky

Beneath The Texas Sky Texas Love Song

Texas Love Song The Texan's Touch

The Texan's Touch Welcome to Harmony

Welcome to Harmony To Wed In Texas

To Wed In Texas The Widows of Wichita County

The Widows of Wichita County The Comforts of Home

The Comforts of Home The Texan and the Lady

The Texan and the Lady Chance of a Lifetime

Chance of a Lifetime The Secrets of Rosa Lee

The Secrets of Rosa Lee Twisted Creek

Twisted Creek Winter's Camp

Winter's Camp Twilight in Texas

Twilight in Texas Just Down the Road

Just Down the Road The Lone Texan

The Lone Texan Give Me a Texan

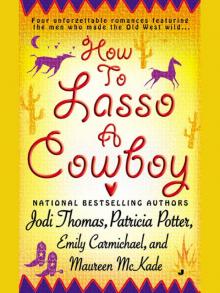

Give Me a Texan How to Lasso a Cowboy

How to Lasso a Cowboy Wild Texas Rose

Wild Texas Rose Finding Mary Blaine

Finding Mary Blaine